Philosophy of Teaching and Learning

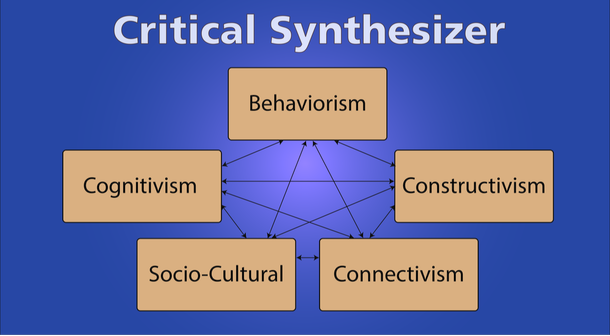

Determining one’s personal teaching and learning philosophy requires consideration of several questions. Such questions include: (a) what is the ultimate or end goal of education, (b) who or what is at the center of the learning process, (c) what is the role of teachers in education, and (d) how should instruction be delivered. Growing up as part of an educator family, teaching and learning philosophies were evident to me at a very young age. When I became a teacher myself, I began to mold these philosophies through my own experiences to understand my own perspectives and beliefs about teaching and learning. Essential to my experiences are the beliefs that all students are capable of learning and that education should provide students with a greater understanding of the world around them. Such an understanding should be capable of adapting and changing throughout learners' lifetimes. Research and theory provide lenses to focus and support my teaching and learning beliefs. This research and theory includes the work of educational reformer Paulo Friere (2011); the work of sociocultural learning scientists Lev Vygotsky (1978), and Sasha Barab and Jonathan Plucker (2002); the work of cognitive psychologist Robert Gagné (1985); and the work of constructivists Brown et al. (1989). These philosophical understandings have molded my teaching philosophy into a critical synthesis of Behaviorism, Cognitivism, Constructivism, Socio-Cultralism, and Connectivism.

The Goal of Education

Education is a path to great responsibility, power, and hope. All learners are different, as are their goals, their motivations, and their learning preferences. Understanding learners' goals, motivations, and preferences helps create instruction that is motivating and beneficial to all learners. When teachers understand learners’ various needs (and wants), they can help learners better understand the world around them. This understanding can lead to lifelong opportunities and learning. The goal of education is to provide students with the critical skills and knowledge needed to help them be successful throughout their lifelong pursuits.

The Center of the Learning Process

Too often in education, I have seen teachers place themselves at the center of the learning process and I believe this is not the best way to effectively teach. The tradition of being the “sage on the stage” is no longer appropriate given the wealth of educational research and resources that instructors have access to. Continuing to place the instructor at the center of the learning process creates a “banking concept” of education (Freire, 2011). The banking concept is a poor structure for education because it dehumanizes learners, turning them into receptacles of information; teachers are treated as guardians of knowledge, who open the vault door of information and let a little bit of knowledge out to be deposited into the minds of students. After a sufficient amount of information has been deposited, these guardians of education then provide students with an assessment, a kind of deposit slip, to see how much information students can recall. The banking concept of education views educator and learner as oppositional, and makes the assumption that teachers know everything, and students know nothing (or at least much less than the instructor), which is at the very least oppressive. I believe students deserve a system of education that is both liberating and humanist, a system that places them at the center of instruction, and allows them to act as active agents, instead of passive participants, in their own education.

The Role of Teachers

Once teachers have removed themselves from the “sage on the stage” role, they can claim a stronger educational leadership role as the “guide on the side.” When educators and learners are no longer oppositional forces in the classroom, they can understand themselves as two halves of a polarity. This new-found relationship creates an environment in which learning happens through learners and instructors working together to form new understandings. This kind of learning environment is supported by sociocultural learning theory and constructivism. Vygotsky (1978) suggests that learning happens through social and cultural interaction. This is a better perspective than the “traditional, entity-based theories, [which] placed knowledge in the head of the learner, [and] led to the creation of educational systems that focused on transmitting content into individual minds” (Barab & Plucker, 2002, p. 165). When teachers understand that students have knowledge, understanding, or views that differ from theirs, then both parties can be active participants in the learning process. This creates a stronger “relational model” that emphasizes “fully contextualized experience through which individuals, environments, and the sociocultural structures and relations transact” to form learning (Barab & Plucker, 2002, p. 178).

Rejecting the tradition of the banking concept does not mean instructors should make learning entirely experiential. There are some contexts in which it is important for instructors to transfer knowledge to learners. For this reason, I subscribe to the idea “that situations actually co-produce knowledge (along with cognition) through activity” (Brown, Collins, and Duguid, 1989). Gagné's nine events of instruction can provide the teacher/learner polarity with a framework for understanding learning activities, but I recognize that these steps may not always be appropriate for every lesson, every learner, or every environment (Gagné, 1985, in Lowther & Ross, 2012). Such frameworks, however, can help the teacher/learner understand how learning activities relate to instructional objectives, and provide guidance for developing engaging and effective learning scenarios.

Delivering Instruction

One focus of my research is incorporating play, exploration, and experimentation into instruction. Play often has a non-academic connotation. I use “play” in the way Rieber, Smith, and Noah use “serious play,” meaning to “voluntarily devote enormous amounts of time, energy and commitment [to a task] and at the same time derive great enjoyment from experience” (1998, para. 4). One needs only to look at children at play to understand the importance play has in education: “throughout social and behavioural science discourse on social and cognitive development, gameplay is regarded as an important arena for the development and formation of thinking, identities, values and norms” (Arnseth, 2006). Yet, that importance is lost, or at least ignored, as learners get older. There are many ways in which play can use technology to enhance learning. Technology can provide beneficial personalized learning activities that promote exploration, experimentation. and joyful learning. To borrow a quote from one of my favorite documentaries, “Everybody, even Grandma, games – meaning checkers, cards, if not now, in the past. Show me even a freakin’ nun or a hermit who hasn’t done cards or checkers” (Gordon, 2007). Learning should feel like a game, instead of a chore.

Such implementation of play for learning can be difficult due to a misunderstanding of play in various cultures. I would argue that a challenge of any teaching/learning approach is adapting approaches to different cultural norms. Games seem to present a universal joy in all cultures and experiences that are engaging. Henrie, Halverson, and Graham (2015) claimed that measuring how engaged learners are in technology-mediated learning is difficult. Yet, play could bring an aspect of engagement to blended learning that has untapped potential. One version of this play that others have experimented with is gamification. While some academics feel as though gamification is simply “bells and whistles” (Boulet, 2016), I argue there is a reason young and adolescent learners dream of owning luxury sports cars instead of beat-up clunkers — luxury cars come with more bells and whistles. Being able to deliver instruction that is enjoyable and engaging means that educators must be able to move from a one-size fits all learning approach to an approach based on the abilities, interests, and goals of their learners. Such learning presents learners with the opportunity to "play" with their education.

Conclusion

Teaching and learning are not as oppositional as they are commonly treated. Teaching and learning are instead two parts of a polarity that together create education. Teachers can learn and learners can teach. It is the interaction of these activities that creates an educational environment that is effective and engaging. Sociocultural learning theory suggests that learning happens through such interactions. Despite these interactions’ importance, teachers should still utilize cognitivist, constructivist, and at times even behaviorist or connectivsit theories to help organize learning activities in ways that help learners understand how learning interactions meet learning outcomes and goals. From my experiences in teaching, one way to incorporate this kind of critical synthesis into the classroom is through serious play in open, blended, or personalized learning environments. It is my goal to help create engaging learning experiences for learners and teachers as part of their participation in each other's educational journeys.

References

Arnseth, H. C. (2006). Learning to play or playing to learn – A critical account of the models of communication informing educational research on computer

gameplay. Game Studies, 6.1. Retrieved from http://gamestudies.org/0601/articles/arnseth

Barab, S. A., & Plucker, J. A. (2002). Smart people or smart contexts? Cognition, ability, and talent development in an age of situated approaches to knowing

and learning. Educational Psychologist, 37(3), 165-182.

Boulet, G. (2016). Gamification is simply bells and whistles. eLearn Magazine. Retrieved from http://elearnmag.acm.org/featured.cfm?aid=3013524

Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32-42. DOI:

10.3102/0013189X018001032

Friere, P. (2011). The banking concept of education. In E. B. Hilty (Ed.), Thinking About Schools. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Gagné, R. M. (1985). The conditions of learning (4th ed.). New York, NY: Holt, Reinhart & Winston

Gordon, S. (Director). (2007). King of Kong [Motion Picture]. United States: New Line.

Henrie, C. R., Halverson, L. R., & Graham, C. R. (2015). Measuring student engagement in technology-mediated learning: A review. Computers and Education,

90, 36-53. Retrieved from https://www.deepdyve.com/lp/elsevier/measuring-student-engagement-in-technology-mediated-learning-a-review-

aGwlSTs21j?key=elsevier

Lowther, D. L., & Ross, S. M. (2012). Instructional designers and P-12 technology integration. In R. A. Reiser and J. V. Dempsey (Eds.), Trends and Issues in

Instructional Design and Technology (3rd ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Rieber, L. P., Smith, L., & Noah, D. (1998). The value of serious play. In R. West (Ed.), Foundations of Learning and Instructional Design Technology (1st ed.).

Available at https://lidtfoundations.pressbooks.com/

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman (Eds.).

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

The Goal of Education

Education is a path to great responsibility, power, and hope. All learners are different, as are their goals, their motivations, and their learning preferences. Understanding learners' goals, motivations, and preferences helps create instruction that is motivating and beneficial to all learners. When teachers understand learners’ various needs (and wants), they can help learners better understand the world around them. This understanding can lead to lifelong opportunities and learning. The goal of education is to provide students with the critical skills and knowledge needed to help them be successful throughout their lifelong pursuits.

The Center of the Learning Process

Too often in education, I have seen teachers place themselves at the center of the learning process and I believe this is not the best way to effectively teach. The tradition of being the “sage on the stage” is no longer appropriate given the wealth of educational research and resources that instructors have access to. Continuing to place the instructor at the center of the learning process creates a “banking concept” of education (Freire, 2011). The banking concept is a poor structure for education because it dehumanizes learners, turning them into receptacles of information; teachers are treated as guardians of knowledge, who open the vault door of information and let a little bit of knowledge out to be deposited into the minds of students. After a sufficient amount of information has been deposited, these guardians of education then provide students with an assessment, a kind of deposit slip, to see how much information students can recall. The banking concept of education views educator and learner as oppositional, and makes the assumption that teachers know everything, and students know nothing (or at least much less than the instructor), which is at the very least oppressive. I believe students deserve a system of education that is both liberating and humanist, a system that places them at the center of instruction, and allows them to act as active agents, instead of passive participants, in their own education.

The Role of Teachers

Once teachers have removed themselves from the “sage on the stage” role, they can claim a stronger educational leadership role as the “guide on the side.” When educators and learners are no longer oppositional forces in the classroom, they can understand themselves as two halves of a polarity. This new-found relationship creates an environment in which learning happens through learners and instructors working together to form new understandings. This kind of learning environment is supported by sociocultural learning theory and constructivism. Vygotsky (1978) suggests that learning happens through social and cultural interaction. This is a better perspective than the “traditional, entity-based theories, [which] placed knowledge in the head of the learner, [and] led to the creation of educational systems that focused on transmitting content into individual minds” (Barab & Plucker, 2002, p. 165). When teachers understand that students have knowledge, understanding, or views that differ from theirs, then both parties can be active participants in the learning process. This creates a stronger “relational model” that emphasizes “fully contextualized experience through which individuals, environments, and the sociocultural structures and relations transact” to form learning (Barab & Plucker, 2002, p. 178).

Rejecting the tradition of the banking concept does not mean instructors should make learning entirely experiential. There are some contexts in which it is important for instructors to transfer knowledge to learners. For this reason, I subscribe to the idea “that situations actually co-produce knowledge (along with cognition) through activity” (Brown, Collins, and Duguid, 1989). Gagné's nine events of instruction can provide the teacher/learner polarity with a framework for understanding learning activities, but I recognize that these steps may not always be appropriate for every lesson, every learner, or every environment (Gagné, 1985, in Lowther & Ross, 2012). Such frameworks, however, can help the teacher/learner understand how learning activities relate to instructional objectives, and provide guidance for developing engaging and effective learning scenarios.

Delivering Instruction

One focus of my research is incorporating play, exploration, and experimentation into instruction. Play often has a non-academic connotation. I use “play” in the way Rieber, Smith, and Noah use “serious play,” meaning to “voluntarily devote enormous amounts of time, energy and commitment [to a task] and at the same time derive great enjoyment from experience” (1998, para. 4). One needs only to look at children at play to understand the importance play has in education: “throughout social and behavioural science discourse on social and cognitive development, gameplay is regarded as an important arena for the development and formation of thinking, identities, values and norms” (Arnseth, 2006). Yet, that importance is lost, or at least ignored, as learners get older. There are many ways in which play can use technology to enhance learning. Technology can provide beneficial personalized learning activities that promote exploration, experimentation. and joyful learning. To borrow a quote from one of my favorite documentaries, “Everybody, even Grandma, games – meaning checkers, cards, if not now, in the past. Show me even a freakin’ nun or a hermit who hasn’t done cards or checkers” (Gordon, 2007). Learning should feel like a game, instead of a chore.

Such implementation of play for learning can be difficult due to a misunderstanding of play in various cultures. I would argue that a challenge of any teaching/learning approach is adapting approaches to different cultural norms. Games seem to present a universal joy in all cultures and experiences that are engaging. Henrie, Halverson, and Graham (2015) claimed that measuring how engaged learners are in technology-mediated learning is difficult. Yet, play could bring an aspect of engagement to blended learning that has untapped potential. One version of this play that others have experimented with is gamification. While some academics feel as though gamification is simply “bells and whistles” (Boulet, 2016), I argue there is a reason young and adolescent learners dream of owning luxury sports cars instead of beat-up clunkers — luxury cars come with more bells and whistles. Being able to deliver instruction that is enjoyable and engaging means that educators must be able to move from a one-size fits all learning approach to an approach based on the abilities, interests, and goals of their learners. Such learning presents learners with the opportunity to "play" with their education.

Conclusion

Teaching and learning are not as oppositional as they are commonly treated. Teaching and learning are instead two parts of a polarity that together create education. Teachers can learn and learners can teach. It is the interaction of these activities that creates an educational environment that is effective and engaging. Sociocultural learning theory suggests that learning happens through such interactions. Despite these interactions’ importance, teachers should still utilize cognitivist, constructivist, and at times even behaviorist or connectivsit theories to help organize learning activities in ways that help learners understand how learning interactions meet learning outcomes and goals. From my experiences in teaching, one way to incorporate this kind of critical synthesis into the classroom is through serious play in open, blended, or personalized learning environments. It is my goal to help create engaging learning experiences for learners and teachers as part of their participation in each other's educational journeys.

References

Arnseth, H. C. (2006). Learning to play or playing to learn – A critical account of the models of communication informing educational research on computer

gameplay. Game Studies, 6.1. Retrieved from http://gamestudies.org/0601/articles/arnseth

Barab, S. A., & Plucker, J. A. (2002). Smart people or smart contexts? Cognition, ability, and talent development in an age of situated approaches to knowing

and learning. Educational Psychologist, 37(3), 165-182.

Boulet, G. (2016). Gamification is simply bells and whistles. eLearn Magazine. Retrieved from http://elearnmag.acm.org/featured.cfm?aid=3013524

Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32-42. DOI:

10.3102/0013189X018001032

Friere, P. (2011). The banking concept of education. In E. B. Hilty (Ed.), Thinking About Schools. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Gagné, R. M. (1985). The conditions of learning (4th ed.). New York, NY: Holt, Reinhart & Winston

Gordon, S. (Director). (2007). King of Kong [Motion Picture]. United States: New Line.

Henrie, C. R., Halverson, L. R., & Graham, C. R. (2015). Measuring student engagement in technology-mediated learning: A review. Computers and Education,

90, 36-53. Retrieved from https://www.deepdyve.com/lp/elsevier/measuring-student-engagement-in-technology-mediated-learning-a-review-

aGwlSTs21j?key=elsevier

Lowther, D. L., & Ross, S. M. (2012). Instructional designers and P-12 technology integration. In R. A. Reiser and J. V. Dempsey (Eds.), Trends and Issues in

Instructional Design and Technology (3rd ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Rieber, L. P., Smith, L., & Noah, D. (1998). The value of serious play. In R. West (Ed.), Foundations of Learning and Instructional Design Technology (1st ed.).

Available at https://lidtfoundations.pressbooks.com/

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman (Eds.).

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.