|

Back in October, I had the wonderful opportunity to attend the AECT conference in the beautiful Kansas City, Missouri. The conference started on Wednesday and went through the weekend, ending on Saturday, but I left for the conference early early because I wanted to see family, and because I attended a workshop on Tuesday. That workshop has inspired this post.

The workshop was offered by a graduate student from a university in the eastern United States, and focused on gamification of learning. It was really cool and I learned a lot; however, there was one thing that happened that I found troublesome. The workshop instructor asked the attendees of his workshop (there were three of us) a question that I have heard many times before in instructional design settings. The question was: Where do you stand on this spectrum of learning theories? He showed us a diagram that looked like this:

SIDEBAR: (Unfortunately, this is not an uncommon question at such conferences, and there have been times that the question has even led to heated debates between various groups of scholars. To be succinct, I think this debate is a dangerous waste of time for a field that has so much potential, and can accomplish so much more than deciding which approach to learning is best. Yet, I want to weigh in on the debate and explain why all sides are both simultaneously wrong, and right, about their stances. Let’s go back to my conference experience).

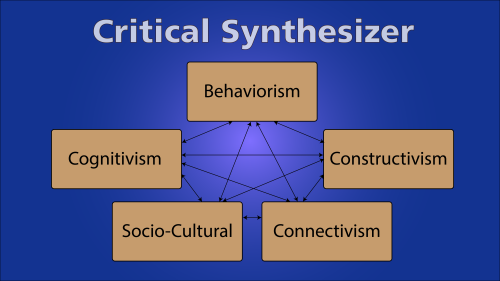

The workshop instructor began by stating his own stance on learning theories. He explained (in a weird kind of instructional design hipster fashion) that he used to be to the far right of the spectrum, even past Constructivism, but has since moved a little more to the left. Next he asked a friend of mine from Virginia Tech for her answer. She responded along the lines of, “Well, I have raised one husband, two dogs, and three kids, so I know Behaviorism works!” She went on to testify of the power of punishment and reward for furthering the learning of students, even pulling in some examples from learning through video games - which I appreciated. Next, the instructor asked one of my colleagues from BYU the same question. Being in the same program, her response did not much surprise me. She stated that she was somewhere between Cognitivism and Constructivism, and really kind of floats back and forth between them. In my opinion, this was by far the best response so far. HOWEVER, I could see from the look in the eyes of the instructor and my friend from Virginia Tech, that sides were already starting to form for the debate. The instructor turned to me and asked, “Cecil, how about you? Where do you fall?” The question made me feel as if I were being drafted for war, and my decision would tip the scales toward victory. I took a deep breath and said, “I think each of the learning theories you have on the board makes some dangerous assumptions about what is and is not considered learning, and that they all have too narrow of a view concerning the responsibilities of both learners and teachers. So, I consider myself to be a critical synthesizer.”

My friend from Virginia Tech responded instantly, “Ooh! I like that! Can I use it?” I told her that I’d be more than happy to let her use it, just give me credit.

The instructor asked me to clarify. What does it mean to be a critical synthesizer? Well, here goes:

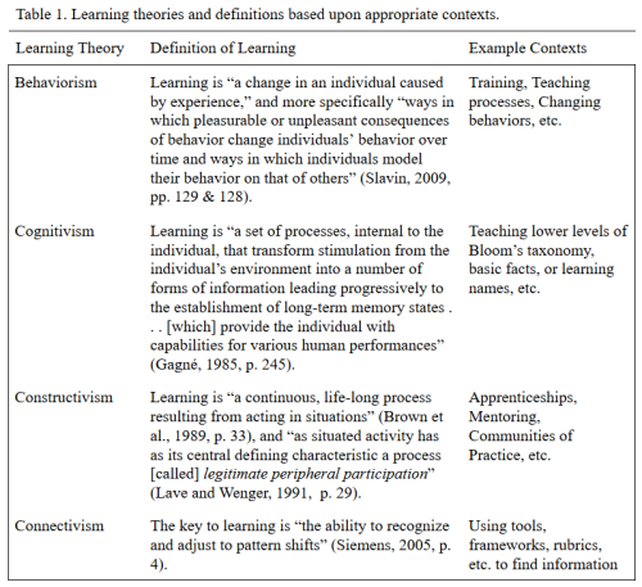

Being a critical synthesizer is similar to what Yanchar and Gabbitas (2011) describe as practicing “critical flexibility.” They describe critical flexibility as the act of taking a “critical stance towards one’s own design sense and an awareness of alternative views that may facilitate the gradual development of one’s practice” (p. 388). Critical flexibility is important to the design and development of instruction, but works less well for guiding the act of instruction. By contrast, a critical synthesizer can change his or her approach to learning based upon the changing demands of a learning context. The critical synthesizer realizes, like the critically flexible designer, that various learning theories and movements have their uses, but using only one approach, or trying to use all of the approaches at once, creates binds in critical assumptions and/or practical applications for learning. The critical synthesizer moves from theory to theory and approach to approach based upon the demands of a learning context. Table 1 identifies some of the contexts and views of learning based upon some of the most popular theories and approaches.

Given the ways in which learning in different contexts can overlap, it is important that educators take a broad approach to learning, understanding that it can have different implications under different circumstances. Learning how to act in elementary school, for example, is vastly different than learning to fly a plane. Taking the same approach to each learning scenario would not only be inappropriate, but foolish. If forced to provide a singular definition of learning, I would say I view learning as “a change in knowledge, understanding, or action that can occur under various circumstances and in various contexts.” Planning for various contexts requires educators to illustrate a critical understanding of the learning context, and a critical synthesis of learning theories and approaches.

I hope that as our field continues to mature, we will seek out less polarization of learning theories, and more compromise and understanding of the ways in which different learning theories can offer insight into different learning situations. Teaching and learning can be difficult concepts to understand, and both have a variety of explanations and approaches. But if educators and instructional designers are going to be prepared to overcome such difficulties they will need learn to become critical synthesizers who use the strengths of various approaches to meet the needs of their various learners in various situations. References Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational researcher, 18(1), 32-42. Gagné, R. M. (1985). A theory of instruction. The conditions of learning and theory of instruction (pp. 243-258). Fort Worth, Holt, Rinehart & Winston, Inc. Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. New York: Cambridge University Press. Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 2(1). Slavin, R. E. (2009). Behavioral theories of learning. Educational psychology: Theory and practice (9th ed., pp. 126-155). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. Yanchar, S. C., & Gabbitas, B. W. (2011). Between eclecticism and orthodoxy in instructional design. Educational Technology Research and Development, 59, pp. 383-398.

0 Comments

|

About

This blog presents thoughts that Cecil has concerning current projects, as well as musings that he wants to get out for future projects. For questions or comments on his posts, please go to his Contact page. Archives

April 2024

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed