Navigating the Landscape of Blended and Virtual Teaching: Competencies for Effective Practice3/11/2024 As educators, we are experiencing a dynamic shift in teaching methodologies, propelled by the rapid integration of technology in educational settings. Blended and virtual learning environments have become increasingly prevalent post-pandemic, demanding a reevaluation of traditional teaching competencies and the cultivation of new skills tailored to these modern modalities. As someone deeply immersed in exploring the nexus between technology and pedagogy, I find myself continually reflecting on the evolving landscape of educational technology and the skills teachers need to navigate such a shifting landscape. I've been reviewing the synthesis of literature on online (OL) and blended (BL) teaching competencies from Pulham and Graham (2018) and Pulham et al. (2018) in preparation for an upcoming presentation for the Indiana Department of Education. These studies provide valuable insights into the core skills necessary for educators to thrive in modern digital domains. Their analyses underscore personalized learning as a cornerstone competency, with sub-domains such as pacing, curriculum, scheduling, and learning styles emerging as focal points for research and practice. While the effectiveness of catering to individual learning needs remains debated, attention to pacing, curriculum design, and scheduling offers promising avenues for enhancing personalized learning experiences within blended and virtual settings. Importantly, the syntheses highlight nuanced distinctions between BL and OL teaching competencies, emphasizing the need for targeted training and support tailored to each modality. BL teaching places a premium on instructional design that seamlessly integrates face-to-face and online components, whereas OL teaching requires a deeper focus on crafting engaging digital learning experiences. Recognizing these differences is crucial for guiding teacher preparation programs to equip educators with the diverse skill sets needed to navigate the complexities of blended and virtual instruction effectively. Moving forward, professional development must be grounded in real-world classroom observations and collaboration with educators who have experienced refining technology-infused teaching applications. Teacher education programs must seize the opportunity to integrate blended and online competencies into their curricula, ensuring that all pre-service teachers are equipped with the requisite skills to thrive in 21st-century learning environments. Support for in-service teachers must provide theoretical foundations while leveraging these teachers' experiences during the pandemic - helping them to see how they can transform in-person learning practices through overcoming the challenges they experienced during emergency remote teaching or helping them to combine virtual learning victories with their already effective in-person strategies. By embracing the paradigm shift toward technology-infused learning post-pandemic and fostering a culture of continuous learning and adaptation, we can empower educators to unlock the full potential of technology in transforming education. As we navigate the ever-evolving landscape of educational technology and attempt to help teachers navigate it, it is imperative that we remain steadfast in our commitment to equipping educators with the competencies needed to excel in blended and virtual teaching environments. By embracing personalized learning, acknowledging the nuances between modalities, and refining competency frameworks to align with the demands of digital pedagogy, we can pave the way for a future where technology serves as a catalyst for innovation and access to quality education for all.

0 Comments

Google Slides to the Full Slideshow (PDF below): https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1F-U62vtkuFpnW1Rj1bdCqeu2F3fOpG-0/edit?usp=sharing&ouid=106061852616377032986&rtpof=true&sd=true In the rapidly evolving landscape of education, the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has emerged as a transformative force, offering a myriad of possibilities to enhance teaching and learning. As a professor deeply immersed in the realms of educational technology and secondary education, it is my pleasure to distill the essence of our extensive exploration into AI's impact on education, from its definitional nuances to its ethical considerations. The heart of our journey forward lies in understanding the potential of AI in education. We must delve into the intricate ways AI fosters personalized learning experiences, adapts to individual needs, and revolutionizes the traditional paradigms of education. From intelligent tutoring systems to the power of augmented and virtual reality, AI is ushering in an era where education is no longer a one-size-fits-all endeavor but a dynamic, tailored experience for each student. Yet, this transformative journey is not without its ethical considerations. As stewards of education, we bear the responsibility of addressing privacy concerns, mitigating biases, and championing fairness in AI algorithms. Our exploration into the ethical dimensions of AI underscores the imperative for educators and institutions to navigate the AI landscape with a keen eye on responsible and ethical practices. Looking ahead, we find ourselves on the cusp of a new educational frontier. The future of AI in education promises an array of emerging technologies, from AI-driven curriculum design to the assessment of non-cognitive skills. Our predictions and possibilities sketch a landscape where education is not confined by traditional boundaries but opens up avenues for lifelong learning, global collaboration, and enhanced accessibility. As we stand on the brink of this transformative future, it becomes paramount for educators and institutions to prepare for the next wave of educational technology. Professional development, data privacy measures, and ethical guidelines will form the cornerstone of navigating this new era, ensuring that we harness the power of AI responsibly for both ourselves and our students. Investment in infrastructure, adherence to ethical frameworks, and a commitment to ongoing research and evaluation will guide us toward a future where AI in education is a force for positive change. In essence, the key takeaways from our exploration converge on the imperative of embracing the AI revolution in education. The potential is vast, the ethical considerations are nuanced, and the future is bright. Let us, as educators, not only witness but actively participate in shaping this transformative journey toward a more dynamic, equitable, and technologically empowered educational landscape. Thank you!

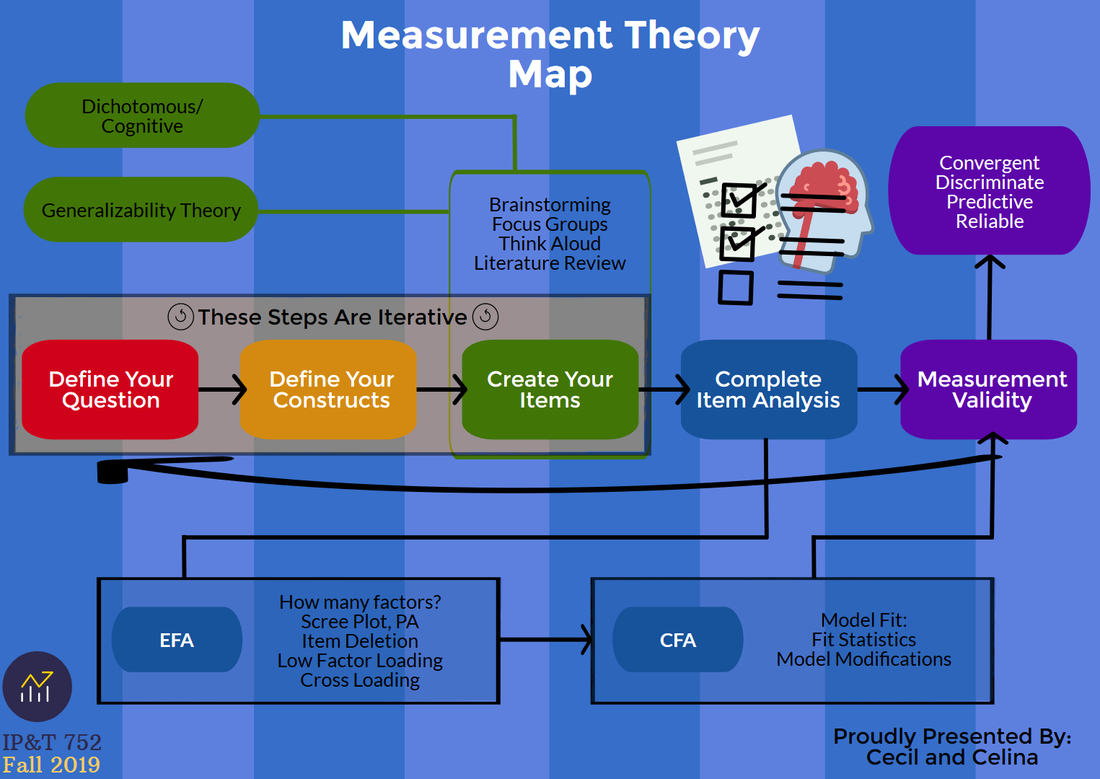

Last semester in my Measurement Theory class, we were given a challenge to take everything we had learned - basically the process of creating a measurement tool including: defining constructs, conducting EFAs, conducting CFAs, different reasons and ways to do so, etc. - and condense it all down to a single page. Knowing that there was maybe too much information to condense it to a single type-written page, I got a bit creative and created a single page using PiktoChart and H5P. After sharing it with the class, they helped me get more information for the graphic so it could be a fairly complete summary of the semester. Unfortunately the H5P account has expired so the interactive map is unavailable, but the static image is posted below for reference. Most of the information for the graphic can be found here.

The graphic is shared here for record keeping and for others to use as they see fit.

Back in October, I had the wonderful opportunity to attend the AECT conference in the beautiful Kansas City, Missouri. The conference started on Wednesday and went through the weekend, ending on Saturday, but I left for the conference early early because I wanted to see family, and because I attended a workshop on Tuesday. That workshop has inspired this post.

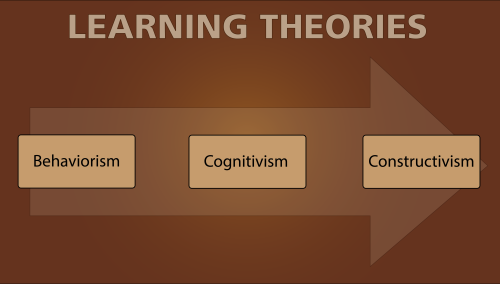

The workshop was offered by a graduate student from a university in the eastern United States, and focused on gamification of learning. It was really cool and I learned a lot; however, there was one thing that happened that I found troublesome. The workshop instructor asked the attendees of his workshop (there were three of us) a question that I have heard many times before in instructional design settings. The question was: Where do you stand on this spectrum of learning theories? He showed us a diagram that looked like this:

SIDEBAR: (Unfortunately, this is not an uncommon question at such conferences, and there have been times that the question has even led to heated debates between various groups of scholars. To be succinct, I think this debate is a dangerous waste of time for a field that has so much potential, and can accomplish so much more than deciding which approach to learning is best. Yet, I want to weigh in on the debate and explain why all sides are both simultaneously wrong, and right, about their stances. Let’s go back to my conference experience).

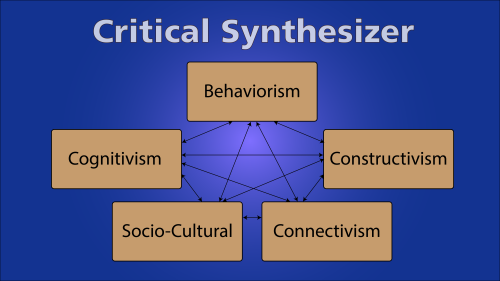

The workshop instructor began by stating his own stance on learning theories. He explained (in a weird kind of instructional design hipster fashion) that he used to be to the far right of the spectrum, even past Constructivism, but has since moved a little more to the left. Next he asked a friend of mine from Virginia Tech for her answer. She responded along the lines of, “Well, I have raised one husband, two dogs, and three kids, so I know Behaviorism works!” She went on to testify of the power of punishment and reward for furthering the learning of students, even pulling in some examples from learning through video games - which I appreciated. Next, the instructor asked one of my colleagues from BYU the same question. Being in the same program, her response did not much surprise me. She stated that she was somewhere between Cognitivism and Constructivism, and really kind of floats back and forth between them. In my opinion, this was by far the best response so far. HOWEVER, I could see from the look in the eyes of the instructor and my friend from Virginia Tech, that sides were already starting to form for the debate. The instructor turned to me and asked, “Cecil, how about you? Where do you fall?” The question made me feel as if I were being drafted for war, and my decision would tip the scales toward victory. I took a deep breath and said, “I think each of the learning theories you have on the board makes some dangerous assumptions about what is and is not considered learning, and that they all have too narrow of a view concerning the responsibilities of both learners and teachers. So, I consider myself to be a critical synthesizer.”

My friend from Virginia Tech responded instantly, “Ooh! I like that! Can I use it?” I told her that I’d be more than happy to let her use it, just give me credit.

The instructor asked me to clarify. What does it mean to be a critical synthesizer? Well, here goes:

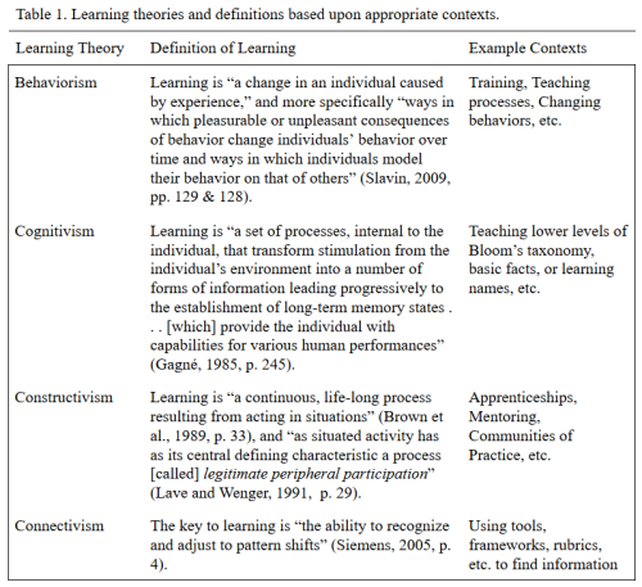

Being a critical synthesizer is similar to what Yanchar and Gabbitas (2011) describe as practicing “critical flexibility.” They describe critical flexibility as the act of taking a “critical stance towards one’s own design sense and an awareness of alternative views that may facilitate the gradual development of one’s practice” (p. 388). Critical flexibility is important to the design and development of instruction, but works less well for guiding the act of instruction. By contrast, a critical synthesizer can change his or her approach to learning based upon the changing demands of a learning context. The critical synthesizer realizes, like the critically flexible designer, that various learning theories and movements have their uses, but using only one approach, or trying to use all of the approaches at once, creates binds in critical assumptions and/or practical applications for learning. The critical synthesizer moves from theory to theory and approach to approach based upon the demands of a learning context. Table 1 identifies some of the contexts and views of learning based upon some of the most popular theories and approaches.

Given the ways in which learning in different contexts can overlap, it is important that educators take a broad approach to learning, understanding that it can have different implications under different circumstances. Learning how to act in elementary school, for example, is vastly different than learning to fly a plane. Taking the same approach to each learning scenario would not only be inappropriate, but foolish. If forced to provide a singular definition of learning, I would say I view learning as “a change in knowledge, understanding, or action that can occur under various circumstances and in various contexts.” Planning for various contexts requires educators to illustrate a critical understanding of the learning context, and a critical synthesis of learning theories and approaches.

I hope that as our field continues to mature, we will seek out less polarization of learning theories, and more compromise and understanding of the ways in which different learning theories can offer insight into different learning situations. Teaching and learning can be difficult concepts to understand, and both have a variety of explanations and approaches. But if educators and instructional designers are going to be prepared to overcome such difficulties they will need learn to become critical synthesizers who use the strengths of various approaches to meet the needs of their various learners in various situations. References Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational researcher, 18(1), 32-42. Gagné, R. M. (1985). A theory of instruction. The conditions of learning and theory of instruction (pp. 243-258). Fort Worth, Holt, Rinehart & Winston, Inc. Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. New York: Cambridge University Press. Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 2(1). Slavin, R. E. (2009). Behavioral theories of learning. Educational psychology: Theory and practice (9th ed., pp. 126-155). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. Yanchar, S. C., & Gabbitas, B. W. (2011). Between eclecticism and orthodoxy in instructional design. Educational Technology Research and Development, 59, pp. 383-398. We are completing an exercise in class that reminds me just how hard writing can be. The goal of the exercise is to write an introduction to a research question in such a way that it logically leads to the research question.

The introduction should be shaped like a funnel, starting broad and then ending by arriving at the narrowly constructed research question. I think I may struggle so much with this because my research question may still be too broad, so it’s difficult to narrow my funnel. Yet, here is where I’m at with the exercise. Step 1 - The Question I began by writing my research question down; however, I will not post it here in case you want to try and test my funnel yourself. You can see my research question in my previous blog post. Step 2 - Creating Levels I began writing the levels that would be needed to introduce my question. Here they are: Lvl: For many U.S. citizens, education is the focus of the first 18 years of their lives. In fact, most states have Compulsory Education Laws Lvl: We worry more about outcomes than experiences. Lvl: But there may be a way to do both. Lvl: The psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi describes a feeling of complete and energized focus in an activity that has a high level of enjoyment and fulfillment that he calls Flow. Lvl: Flow Theory states that there are eight mental states that can be experienced during any activity. Lvl: Researchers have analyzed how components of Flow impact work and leisure, from factory work to surgery, and from active-leisure (e.g., playing a musical instrument, playing a sport, or carving) to watching tv. Lvl: But little has been done to observe: “The Question” Step 3 - The Rough Funnel I then connected the steps into two introductory paragraphs. Here is the funnel: Education is the primary focus of the first 18 years of most U.S. citizens’ lives. In fact, most states have Compulsory Education Laws that require school attendance for students between certain ages. In evaluating and planning for the education of these K-12 students, social and political forces tend to focus much more on the outcomes of attending school than on the emotional experiences of attending school. Focusing on outcomes is incredibly important; however, because states mandate that students spend somewhere between 8 and 13 years enrolled in an educational institution, we should focus on making these years academically enriching and enjoyable. One of the reasons K-12 education can be un-enjoyable is because it does not meet the personalized needs and desires of individual learners. Personalizing instruction based on students’ abilities and providing students with clear feedback concerning their progression towards educational goals can both improve educational outcomes and make education more enjoyable. Flow Theory can be used to create a framework for personalizing education in a way that makes K-12 education enriching and enjoyable. The psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi describes “Flow” as the feeling of complete and energized focus, accompanied by a high level of enjoyment and fulfillment. Csíkszentmihályi claims that Flow is attainable during any activity if a task’s difficulty matches a person’s ability level and if a person can receive nearly immediate feedback about the improvement of his or her abilities. Learning in a K-12 classroom is an activity that could also benefit from Flow Theory. Researchers have analyzed how components of Flow Theory affect the outcomes and enjoyment of work and leisure, but little research has been done to observe: ____________. Step 4 - Test the Funnel I asked several people to read my funnel to see if they could arrive at my question. My wife had the most success at arriving at my question, but she has a pretty biased perspective and can fill in the gaps my brain makes. I also asked a couple of fraternity brothers; they got pretty close. My classmates and advisor felt like the second paragraph was a bit derailing with all of the Flow Theory stuff, so I worked to cut it down. Step 5 - Revise the Funnel I took the feedback from Step 4 and arrived and this new version of the funnel: Education is a primary focus of the first 18 years of most U.S. citizens’ lives. In fact, most states have Compulsory Education Laws that require school attendance for students between certain ages. In evaluating and planning for the education of these K-12 students, social and political forces tend to focus much more on the outcomes of attending school than on the emotional experiences of attending school. Focusing on outcomes is incredibly important; however, because states mandate that students spend somewhere between 8 and 13 years enrolled in an educational institution, it is important to focus on making these years academically enriching and enjoyable. Students may find the K-12 years to be unenjoyable because the experience leaves them feeling unfulfilled. Schools can likely change this if they will match individual students’ abilities to the learning tasks they are asked to complete. Csíkszentmihályi (1990) says that matching individual ability level to task difficulty creates Flow, the feeling of complete and energized focus accompanied by a high level of enjoyment and fulfillment. Researchers have shown that components of Flow increased the feelings of enjoyment and fulfillment for work and leisure activities (Csíkszentmihályi, 1994), but little research has been done to answer the question: ______. Step 6 - Repeat Steps 4 and 5 to Satisfaction I’m not entirely convinced my funnel is done, but I tested it with many more people this time around, ranging from K-12 and Higher Ed. educators to other graduate students, and I even added a very healthy dose of help from some former students working in education or on undergraduate degrees. There seemed to be much more consensus this time around, and I’m thankful for all the help I received. Guesses close to the mark included: “Whether utilizing the Flow approach to education will positively impact students’ success during and after primary and secondary education.” - Former K-12 student and Valedictorian “If all students were impassioned by the subjects they were studying and projects they were completing, how much more would they learn?” - Former K-12 student working in education “How beneficial Flow could be to the students of today, and how can it maximize their ability to adapt and learn as they move into the future?” - K-12 pre-sevice teacher “How can schools increase Flow?” - K-12 teacher “Where has Flow been show to be effective, and does this research have enough trasnferability to K-12 to show it would be worth the time of [implementation and testing]?” - Fellow graduate student Guesses further away were: “Is our current system of education providing enough mental stimulation for our children and teaching them not only to learn but to enjoy the process of learning, or is our primary focus on improving test scores with little to no regard for students mental aptitude and involvement; and if the latter is the case, is it possible to overhaul our archaic system and shift the focus from test scores to mental involvement?” - Rather jaded former K-12 student “Whether the traditionally structured school day vs. something different has actually led to true achievement.” - K-12 Instructor -AND- “Can we play a game?” - Higher Ed. Instructor |

About

This blog presents thoughts that Cecil has concerning current projects, as well as musings that he wants to get out for future projects. For questions or comments on his posts, please go to his Contact page. Archives

April 2024

Tags

All

|

||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed