|

Download Conference Presentation Slides Here Download AI-Generated TL;DR Slides for the Blog Post Here This week I have the honor and privilege to address the next generation of educators at the Buzz Into Teaching conference at Johnson County Community College. My keynote presentation will embark on a journey into the future of education—a future shaped by the transformative power of Artificial Intelligence (AI). In our exploration of AI's role in education, we will uncover a world of endless possibilities. We will imagine classrooms where learning is personalized to each student's needs, where AI-driven systems adapt in real-time to foster deeper understanding and engagement, and where every teacher in every classroom has an assistant to help, and every student in every classroom has a one-on-one tutor. This vision of personalized learning isn't just a dream; it's a reality made possible by the integration of AI technologies - but only if future educators can learn to strategically integrate these technologies with the tried and true strategies of yesterday's classroom. Looking ahead, we can envision a future where AI revolutionizes nearly every aspect of education, from curriculum design to global collaboration. As we prepare for such transformation, it is essential to equip ourselves with the necessary skills and knowledge to harness the power of AI responsibly. Professional development opportunities, like those provided at the Buzz Into Teaching conference, will be key as we adapt to the changing landscape of education and the world at large. To remain at the forefront of innovation and best practices, we must become explorers and inventors - designers willing to take on new challenges with new approaches. Moreover, advocating for ethical guidelines and standards in AI usage will be paramount to safeguarding the rights and well-being of all students. From safeguarding data privacy to ensuring fairness and equity in algorithmic decision-making, it is our responsibility as educators to navigate these ethical waters with diligence and integrity. The journey ahead is both exciting and challenging. As we stand on the precipice of this technological revolution, my sincere hope is that we can constantly remember the profound impact we as educators have in shaping the future of our students and society as a whole. Together, we can embrace the AI revolution in education with open minds and compassionate hearts, ensuring that every student has the opportunity to thrive in a world powered by knowledge and innovation. A world that will need to accept the benefits of what is artificial, without losing site of what it means to be human. I am sincerely grateful for the opportunity to share this journey with tomorrow's teacher leaders and leader teachers.

Together, may we seek to inspire and empower the next next generation of educators with passion, dedication, curiosity, and humanity.

2 Comments

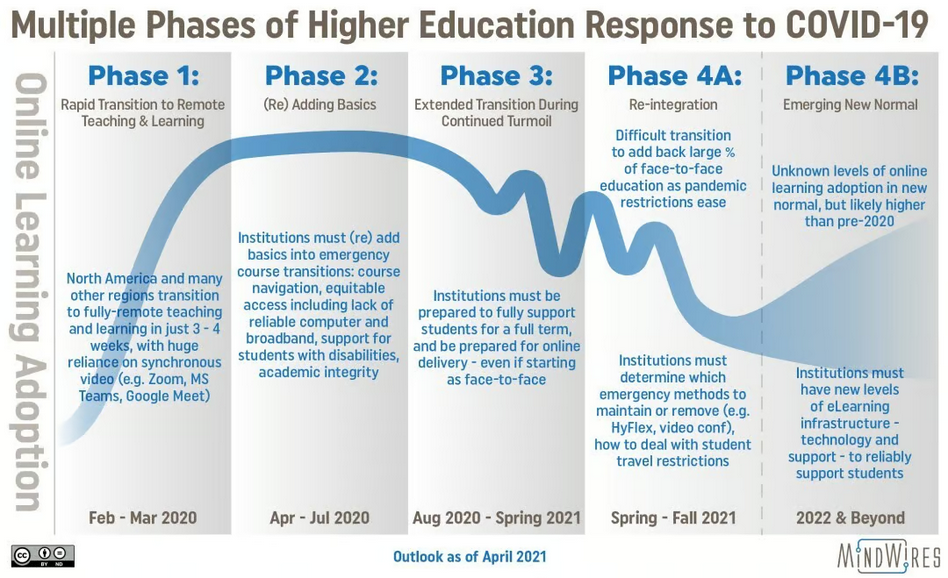

Navigating the Landscape of Blended and Virtual Teaching: Competencies for Effective Practice3/11/2024 As educators, we are experiencing a dynamic shift in teaching methodologies, propelled by the rapid integration of technology in educational settings. Blended and virtual learning environments have become increasingly prevalent post-pandemic, demanding a reevaluation of traditional teaching competencies and the cultivation of new skills tailored to these modern modalities. As someone deeply immersed in exploring the nexus between technology and pedagogy, I find myself continually reflecting on the evolving landscape of educational technology and the skills teachers need to navigate such a shifting landscape. I've been reviewing the synthesis of literature on online (OL) and blended (BL) teaching competencies from Pulham and Graham (2018) and Pulham et al. (2018) in preparation for an upcoming presentation for the Indiana Department of Education. These studies provide valuable insights into the core skills necessary for educators to thrive in modern digital domains. Their analyses underscore personalized learning as a cornerstone competency, with sub-domains such as pacing, curriculum, scheduling, and learning styles emerging as focal points for research and practice. While the effectiveness of catering to individual learning needs remains debated, attention to pacing, curriculum design, and scheduling offers promising avenues for enhancing personalized learning experiences within blended and virtual settings. Importantly, the syntheses highlight nuanced distinctions between BL and OL teaching competencies, emphasizing the need for targeted training and support tailored to each modality. BL teaching places a premium on instructional design that seamlessly integrates face-to-face and online components, whereas OL teaching requires a deeper focus on crafting engaging digital learning experiences. Recognizing these differences is crucial for guiding teacher preparation programs to equip educators with the diverse skill sets needed to navigate the complexities of blended and virtual instruction effectively. Moving forward, professional development must be grounded in real-world classroom observations and collaboration with educators who have experienced refining technology-infused teaching applications. Teacher education programs must seize the opportunity to integrate blended and online competencies into their curricula, ensuring that all pre-service teachers are equipped with the requisite skills to thrive in 21st-century learning environments. Support for in-service teachers must provide theoretical foundations while leveraging these teachers' experiences during the pandemic - helping them to see how they can transform in-person learning practices through overcoming the challenges they experienced during emergency remote teaching or helping them to combine virtual learning victories with their already effective in-person strategies. By embracing the paradigm shift toward technology-infused learning post-pandemic and fostering a culture of continuous learning and adaptation, we can empower educators to unlock the full potential of technology in transforming education. As we navigate the ever-evolving landscape of educational technology and attempt to help teachers navigate it, it is imperative that we remain steadfast in our commitment to equipping educators with the competencies needed to excel in blended and virtual teaching environments. By embracing personalized learning, acknowledging the nuances between modalities, and refining competency frameworks to align with the demands of digital pedagogy, we can pave the way for a future where technology serves as a catalyst for innovation and access to quality education for all.

In the ever-evolving landscape of education, Makerspaces have emerged as transformative hubs, blending the historical essence of tinkering with contemporary pedagogical principles. Originating from humanity's early days of "making activities," Makerspaces are deeply rooted in experiential learning, child development through play, and the empowerment of students as changemakers in a dynamic world.

The recent surge in Makerspaces is a response to the global call for innovative workforces. Stemming from the integration of STEM education, the rise of do-it-yourself communities, and the accessibility of digital fabrication technologies, Makerspaces have become diverse environments for exploration and creation. Whether found in preschools, post-secondary institutions, or community libraries, these spaces foster innovation, creativity, problem-solving, and collaboration. Makerspaces transcend traditional boundaries, offering both formal and informal learning opportunities, and their impact extends beyond affective outcomes, influencing cognitive and psychomotor skills. As we continue to explore Makerspaces, it becomes clear that they hold the key to reshaping how we learn and engage with the world, unlocking the potential for creativity and collaboration in learners of all ages. Read more in my EdTechnica chapter co-authored by my ever wonderful colleagues Dr. Jacob Hall and Dr. Kali Neumann: edtechbooks.org/encyclopedia/makerspaces Short, C. R., Hall, J., & Neumann, K. (2023). Makerspaces. EdTechnica: The Open Encyclopedia of Educational Technology. https://dx.doi.org/10.59668/371.12182 Google Slides Presentation: docs.google.com/presentation/d/17Q8EjFWjW9krMxc8_RFi3s6WzLqOIrDO/edit?usp=sharing&ouid=106061852616377032986&rtpof=true&sd=true

As a professor with a research history in personalized learning, I have witnessed the transformative power of tailoring education to individual needs, preferences, and interests. While personalized learning has been a part of education for centuries, recent advancements in instructional technology have paved the way for a more accessible and effective approach. The slides accompanying this blog post demonstrate that both teachers and students recognize and appreciate the affordances of personalized learning, marking a crucial shift in educational paradigms. The evolution of personalized learning, underscores its potential as a gateway to lifelong learning. The 2017 U.S. National Education Technology Plan redefined personalized learning to emphasize the learner's role in tailoring instruction, emphasizing activities that are meaningful, relevant, and often self-initiated. This learner-centric approach aligns with the call for a dynamic, personalized learning strategy capable of providing a unique and effective learning experience for each individual, fostering the skills needed to promote a lifelong commitment to learning. Technological advancements have given educational institutions the tools to customize learning experiences, but the true power lies in the pedagogical knowledge required to leverage personalized learning effectively. My research, drawing on frameworks and findings presented by experts like Horn and Staker (2014), Graham et al. (2019), and Shemshack et al. (2021), has emphasized the importance of tailoring the time, place, pace, path, and goals of learning. By incorporating learner profiles, previous knowledge, personalized learning paths, and flexible self-paced environments, educators can empower learners to take charge of their education and enhance their self-efficacy. The five dimensions of personalized learning (goals, time, place, pace, and path), illustrate the multifaceted nature of this pedagogical strategy. Understanding what is being personalized, how it is being personalized, who or what is providing personalization, and what the personalization is based on allows educators to create tailored, effective learning experiences. While the potential of personalized learning is vast, ongoing research, as highlighted by Short (2022), Bulger (2016), Watters (2023), and Zhang et al. (2020), is necessary to explore outcomes and ensure technology fulfills its promise of transformational, individualized learning. Read more foundational information about Personalized Learning in my chapter on the topic in EdTechnica co-authored by the brilliant Atikah Shemshack: https://edtechbooks.org/encyclopedia/personalized_learning Short, C. R. & Shemshack, A. (2023). Personalized Learning. EdTechnica: The Open Encyclopedia of Educational Technology. https://dx.doi.org/10.59668/371.11067 Bulger, M. (July 7, 2016). Personalized learning: The conversations we're not having. Data and Society 22(1), 1-29. https://edtechbooks.org/-jkKy Graham, C. R., Borup, J., Short, C. R., & Archambault, L. (2019). K-12 blended teaching: A guide to personalized learning and online integration. Provo, UT: EdTechBooks.org. https://edtechbooks.org/-TiF Horn, M. B., & Staker, H. (2014). Blended: Using disruptive innovation to improve schools. Jossey-Bass. Shemshack, A., Kinshuk & Spector, J. M. (2021). A comprehensive analysis of personalized learning components. Journal of Computers in Education, 1(19). https://edtechbooks.org/-Uwr Short, C. R. (2022). Personalized learning design framework: A theoretical framework for defining, implementing, and evaluating personalized learning. In H. Leary, S. P. Greenhalgh, K. B. Staudt Willet, & M. H. Cho (Eds.), Theories to Influence the Future of Learning Design and Technology. EdTech Books. https://edtechbooks.org/-GBqb Watters, A. (2023). Teaching machines: The history of personalized learning. The MIT Press. Zhang, L., Basham, J. D., & Yang, S. (2020). Understanding the implementation of personalized learning: A research synthesis. Educational Research Review, 31(100339). https://edtechbooks.org/-RLV Google Slides to the Full Slideshow (PDF below): https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1F-U62vtkuFpnW1Rj1bdCqeu2F3fOpG-0/edit?usp=sharing&ouid=106061852616377032986&rtpof=true&sd=true In the rapidly evolving landscape of education, the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has emerged as a transformative force, offering a myriad of possibilities to enhance teaching and learning. As a professor deeply immersed in the realms of educational technology and secondary education, it is my pleasure to distill the essence of our extensive exploration into AI's impact on education, from its definitional nuances to its ethical considerations. The heart of our journey forward lies in understanding the potential of AI in education. We must delve into the intricate ways AI fosters personalized learning experiences, adapts to individual needs, and revolutionizes the traditional paradigms of education. From intelligent tutoring systems to the power of augmented and virtual reality, AI is ushering in an era where education is no longer a one-size-fits-all endeavor but a dynamic, tailored experience for each student. Yet, this transformative journey is not without its ethical considerations. As stewards of education, we bear the responsibility of addressing privacy concerns, mitigating biases, and championing fairness in AI algorithms. Our exploration into the ethical dimensions of AI underscores the imperative for educators and institutions to navigate the AI landscape with a keen eye on responsible and ethical practices. Looking ahead, we find ourselves on the cusp of a new educational frontier. The future of AI in education promises an array of emerging technologies, from AI-driven curriculum design to the assessment of non-cognitive skills. Our predictions and possibilities sketch a landscape where education is not confined by traditional boundaries but opens up avenues for lifelong learning, global collaboration, and enhanced accessibility. As we stand on the brink of this transformative future, it becomes paramount for educators and institutions to prepare for the next wave of educational technology. Professional development, data privacy measures, and ethical guidelines will form the cornerstone of navigating this new era, ensuring that we harness the power of AI responsibly for both ourselves and our students. Investment in infrastructure, adherence to ethical frameworks, and a commitment to ongoing research and evaluation will guide us toward a future where AI in education is a force for positive change. In essence, the key takeaways from our exploration converge on the imperative of embracing the AI revolution in education. The potential is vast, the ethical considerations are nuanced, and the future is bright. Let us, as educators, not only witness but actively participate in shaping this transformative journey toward a more dynamic, equitable, and technologically empowered educational landscape. Thank you!

|

About

This blog presents thoughts that Cecil has concerning current projects, as well as musings that he wants to get out for future projects. For questions or comments on his posts, please go to his Contact page. Archives

April 2024

Tags

All

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed